Illustration 20. One-row bayan.

(from the archive of A. Mirek)

And it was the Soviets, who in 1966, ending decades of self-imposed isolation, burst forth upon the Western music world with stunning aplomb and won the lion's share of trophies at the international accordion competition held in Klingenthal, East Germany. Since then, the Soviets have consistently out-performed other countries at international competitions such as the Grand Prix de l'Accordeon in France, the Trophee Mondial in Spain, and similar events in Castelfidardo Italy, Klingenthal Germany and Kansas City U.S.A. 1 Due to the impressive Soviet successes, the Russian bayan has become the preferred instrument of choice among the greatest international virtuosi of the instrument.

The word bayan was taken after the name of the ninth/tenth-century poet, artist and musician (The Bayan) who first appeared in a troubadour poem, The Story of the Igoreve Regiment. At first the name was used to refer to the ancestor of the modern bayan, the Russian harmonica. The instrument developed with the addition of bellows, register stops, a left-hand manual which later became standardized to include both stradella and free-bass (convertor), and a right-hand manual which increased the number of button rows from three to five.

Ellegaard said, "The Russian word bayan simply means button-accordion. If you look at the Russian concert bayan, there is a very obvious difference in the shape of the instrument. On the bayan, the treble keyboard is mounted more-or-less in the middle -- further out -- which gives you a more convenient arm position. So the shape of the Russian bayan differs from other [chromatic button] accordions."

Ellegaard continued, "[Another] difference between the Russian accordions and the Western accordions is the reeds. The Russian reeds are all mounted on big plates like the reeds on a harmonica; no wax at all. Also the shape of the reeds is different. Russian reeds are rectangular and Italian reeds are conic; so different sonorities are produced. The Russian reeds are fantastic; I must say they have qualities that the Western reeds don't have. But there are also problems with tuning -- the reeds often break. It's very difficult to get them replaced. I've been to Moscow several times to have reeds replaced." 2

The bayan has spread throughout Europe, expanding from Russia to Poland and the Eastern Bloc countries, Scandinavia, France, Spain and Portugal. Today the bayan is slowly making a foothold even in countries such as Austria, Italy, New Zealand and the United States, which traditionally have been exclusively devoted to the piano-accordion. 3

Nikolai Chaikin (b. 1915) is an important Soviet composer who wrote many pieces for bayan, including Sonata No. 1 (1944), Concerto No. 1 (1950), Toccata (1956), Concert Suite (1962), Ukrainian Suite (1970), Concerto No. 2 (1972), and Sonata No. 2.

Many bayanists also composed music for their instrument. Georgy G. Shenderyov (1937 - 1984) wrote Prelude and Toccata (1959). Albin Repnikov (b. 1932) wrote Capriccio (1962), Concert Poem (1966) for bayan and orchestra, and Souvenirs (1974). Alexander Timoshenko (b. 1942) wrote Russian Pictures Suite (1969), Sonata (1971) and Russian Suite (1975).

Yevgeny Derbenko (b. 1949) is best known for his solo compositions for Russian folk instruments, such as Five Russian Popular Prints (1970) and Toccata (1986). The bayanist-composer, Vyacheslav Semyonov (b. 1946), wrote Bulgarian Suite (1975), Guelder Rose (1976), Don Rhapsody I (1977), Don Rhapsody II (1982) and Sonata No. 2 (1995). Anatoly Kusyakov (b. 1945) wrote Sonata No. 1 (1979), Sonata No. 2 (1981) and Winter Sketches -- a suite in six movements. Sergei Berinski (b. 1945) wrote the partita: Also sprach Zarathustra. 4

Among dozens of Soviet composers who have written for the bayan, two deserve special mention: Zolotaryov and Gubaidulina. Although Vladislav Zolotaryov (1942-1975) wrote vocal music, string quartets, compositions for chamber and symphony orchestras and an oratorio (Monument to the Revolution), his works for bayan are considered to be his greatest musical achievements. Lips and Surkov wrote in Anthology of Compositions for Button Accordion, "The creative work of Vl. Zolotaryov can be described as a milestone of the utmost importance for the incontestable progress of accordion music. . . . In his Partita (1968), Six Children's Suites (1969/74), his Sonata No. 2 (1971) and Sonata No. 3 (1972), and Five Compositions (1971), the advantages of the new-type [converter free-bass] accordion have, as never before, been wholly revealed. The instrument has become a full and equal participant in the chamber sphere of art music." 5

Sofia Gubaidulina, born in the Tartar Republic in 1931, is the best-known of all the Soviet composers who have written for the bayan. Dorothy Redepenning wrote, "She did not have an easy life in the Soviet Union. When a critic in 1962 praised her impeccable technique but belittled her intellectual position . . . she was advised by Dmitri Shostakovich to continue following her 'mistaken path.' Gubaidulina took this advice; she held fast to her artistic credo and, as a result, endured bitter privation. In the middle of the 1960's her works began to be played in the West; commissions and prizes soon followed, and from the 1980's she was able to travel regularly." 6

Her works for bayan are De Profundis (1978); Seven Words (1982) for bayan, violoncello and strings; Et exspecto (1986), a sonata in five movements, Silenzio (1992) for bayan, violin and violoncello, In Croce (1992) for cello and bayan (originally written for cello and organ), and Zeitgestalten. During the last few years at least four different CD recordings have been released of Seven Words, on Wergo, Berlin Classics, MCA Records, and RCA Red Seal, in addition to recordings of Silenzio, De Profundis, and Et exspecto which were released on BIS, Elkar, Russian Disc and Lips CD. Several of her works were dedicated to Friedrich Lips, the Russian bayanist, pedagogue and author. 7

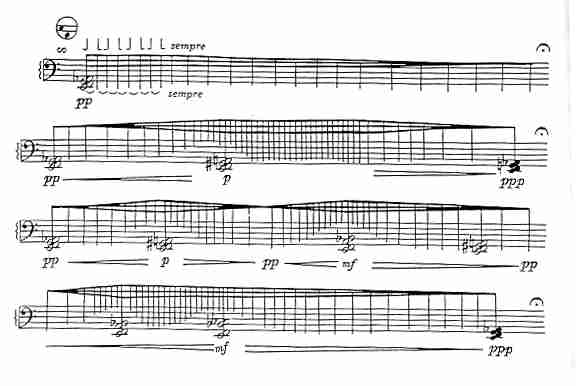

Example 83. Sofia Gubaidulina, De Profundis for solo bayan, first four lines from page one.

copyright 1982. Used by permission of Musikverlag Hans Sikorski.

The degree of respect accorded to the bayan by Soviet composers and audiences is, to a large extent, unheard of in the West. Why have the Soviets had such great success in elevating the bayan from a crude folk instrument to a respected concert instrument, when, throughout most of the Western world, there has been much prejudice toward the instrument among classical musicians and listeners? Part of the answer, I believe, has to do with the Soviet educational system, and the other part has to do with Soviet ideology and culture.

The founding fathers of the U.S.S.R. recognized the importance of quality education, not just for the wealthy, but for all citizens. This resulted in the development of the Soviet school system. All schools were free of charge, from the earliest kindergartens to the highest universities and conservatories. Music education was considered important for children, and those who showed exceptional talent were sent to public music schools, where they received professional musical training. By 1970 the Soviet Union had 3,649 kindergarten music schools (ages three to six), thirty-five middle music schools (ages seven to seventeen), and twenty-four conservatories (ages eighteen to twenty-two), in addition to 1,210 music schools for adults and 206 music colleges. 8 No child was denied first-class training simply because his family was poor, as we sometimes see in the West. 9

Ulrich Schmuelling, the German music publisher, wrote, "Certainly this system of music education is one reason for the incredible results of the interpretation of Soviet musicians. But it would be a mistake to credit the success of Soviet musicians solely with the educational system. One must keep in mind other aspects of Soviet society." 10

In my opinion, the other important factor in the acceptance and development of the bayan in the Soviet Union was the widespread appreciation for its national folk music. Folk music was not considered inferior to serious art music just because it developed from peasant society. The Marxist philosophy, at least in its pure form, demands utmost respect for the working class people and their traditions and the Soviet government decided to support their native folk music culture to help establish a national identity. In fact, the bayan was specifically promoted as the preferred instrument of choice for village social functions such as weddings and dances; the piano, harmonium, organ (as well as the piano-accordion) 11 were considered to be too bourgeois, too Western. 12

In fact, the bayan was regarded so highly by the Soviet government that the Jupiter bayan factory in Moscow was established as an experimental department of the Red Army, and therefore was well-funded. 13

Both classical music and folk music were equally respected by all classes of society, from high-positioned party administrators to factory workers. This was not simply communist propaganda; in the U.S.S.R. the accordion never had the poor reputation that it had in the West.

Schmuelling continued, "The [Soviet] accordion players are concerned with the tradition of their instrument, but also with developing their playing slowly and steadily to an art form without forgetting that their instrument is at heart a folk instrument. In Germany, however, the art of accordion playing developed in a very different way. There was a certain period of time when there was a planned and desired break from the traditional folk music and since that point one differentiates between the artistically less valuable folk music and the artistically higher and important concert music, that is, the so called 'new music.' And because of this there are different groups who oppose each other with confrontation, discussion and disagreement. And so, in Germany, so much energy has been spent differentiating between folk music and concert music, while in the Soviet Union there is no differentiating between folk music and art music. Therefore, the Soviets can put their energies in one direction." 14

I had the pleasure of performing with the great Russian cellist, Mstislav Rostropovich, in May 1996, and during the course of one conversation with him learned that many decades ago he had performed on a government-sponsored concert tour of one year's length with the bayanist Yuri Kazakov. I was surprised to learn that on this tour they did not travel to cities like Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev. Instead, they traveled to small towns and villages in the hinterlands of Siberia.

They performed hundreds of concerts for simple peasant people, occasionally in villages with populations of less than 100. Sometimes they performed in theaters, sometimes in private homes and sometimes in barns. Their program consisted of classical music from Bach to modern twentieth-century works, including pieces based on traditional Russian folk tunes. Rostropovich told me that these concerts were a big event for the villagers; some of the hamlets were so far removed from the nearest city that many residents had never before heard a classical music concert. Rostropovich said that the music he and Kazakov performed, whether familiar or unfamiliar to the listeners, was always well received.

Footnotes:

1 Ulrich Schmuelling, "Vorbemerkung des Herausgebers,"from Friedrich Lips, Die Kunst des Bajanspiels (Kamen, Germany: Schmuelling, 1991), 20-21.

I heard the concert by the Gnessin Music Institute Bayan Orchestra in Kansas City in August 1990 and was truly impressed, as was the classical music editor for the Kansas City newspaper, who wrote, "All right, I'll take the pledge: never again to make disparaging remarks about accordionists. Hearing 14 of them last weekend, plus an electric bass guitarist and a couple of percussionists, made a convert of me. In fact -- dare I say it? -- the concert by the Bayan Orchestra, from the Soviet Union's Gnessin Music Institute may have been the most exciting music-making I've heard in Kansas City."

Scott Cantrell, "Dreaded Accordions Prove Delightful," The Kansas City Star, August 19, 1990.

In addition, the young Soviet players won six trophies out of twelve during the final round of the competition.

2 Mogens Ellegaard, cited in "Interview," The Classical Accordion Society of Canada Newsletter (March 1990), 6.

3 Peter Soave, in conversation with the author on October 8, 1996.

4 Other Soviet bayanist who wrote for their instrument were: V. Bonakov, Vladimir Zubitski, V. Chernikov, J. Shishakov, V. Dikusarov, A. Holminov, V. Shishin, and J. Naimushin.

5 Lips and Surkov, op. cit.

6 Dorothy Redepenning, CD booklet notes for Sofia Gubaidulina: Sieben Worte, In Croce, performed by cellist Julius Berger and accordionist Stefan Hussong, with the Kammerorchester Diagonal, conducted by Florian Rosensteiner (Mainz, Germany: Wergo 1994), 8.

7 Three other professional composers who wrote for bayan are Anatoli Kusiakov, A. Volkov and Gennadi Banshikov. Kusiakov, a professor at the conservatory at Rostov-on-Don, wrote Autumn Landscape, Spring Pictures, and Concerto for Bayan, String Orchestra and Percussion while Banshikov (from St. Petersbug) wrote three sonatas for bayan.

8 Schmuelling, op. cit., 16.

9 However, the Soviet system was not without fault. Jewish and Moslem students were denied education and those children who were accepted -- including good Communist atheists -- were not always allowed to choose the instrument they wished to play. When Natalia Semyonova (the wife of bayanist Vyacheslav Semyonov) was a child, she applied for admission to the State Music School as a piano major. However, her application was denied because the school had already filled its quota of piano students. Instead, she was told to study the Domra, a Russian three-stringed folk instrument similar in sound to the mandolin. Actually, she was lucky to be accepted at all, since Soviet women were routinely denied entrance to music schools; in Russian society their place was considered to be in the home, not on the stage.

Vyacheslav Semyonov, cited by Robert Sattler, a bayan student of V. Semyonov, from a telephone conversation with the author on October 17, 1996.

10 Schmuelling, op. cit., 17.

11 In the 1950s, the Soviet government officially forbid the teaching of piano-accordion in state music schools because the music which was played on it -- tangos, foxtrots and jazz -- was not native to the Soviet people. It became increasingly difficult for piano-accordionists to find any possibility to perform, despite the popularity of this light music with the general populace. In the 1960s the piano-accordion was re-introduced in music education, but today the instrument still suffers from a negative image.

12 Vyacheslav Semyonov, cited by Robert Sattler, op. cit.

13 Johan de With, professor of accordion and music theory at the Conservatory in Groningen, Netherlands, from a lecture at the Groningen Conservatory on September 26, 1996.

14 Schmuelling, op. cit., 20.

| Back to History of the Free-Reed Instruments |

| Back to The Classical Free-Reed, Inc. Home Page |