Illustration 12. Harmonicas.

(from the archive of A. Mirek)

"During the year 1829, J. W. Glier began manufacturing mouth organs at his factory in Klingenthal, Germany. In 1855 the German, Christian Weiss, started producing mouth organs. Finally in 1857 a firm in Trossingen Germany began mass producing harmonicas for the public. At the head of this company was the famous Matthias Hohner. Today the manufacture of harmonicas in Europe is in the sole domain of the Hohner harmonica factory at Trossingen. . . .

"When Hohner first began producing harmonicas, in 1857 his factory produced a mere 650 harmonicas. In 1879 he increased his production to over 700,000 harmonicas. At the turn of the century, the company was producing five million harmonicas annually. Since that time, the Hohner company has expanded their production to over fifty diatonic and chromatic harmonica models . . ."

Despite its popularity among the working class people, the harmonica — for more than one hundred years after its invention — remained little more than a primitive diatonic folk instrument; it could play in only one key at a time. To my knowledge, no classical composers wrote for harmonica until the fourth decade of the twentieth century.

In 1930 the American band leader, John Philip Sousa (1854-1932), wrote a piece for harmonica band, titled The Harmonica Wizard. Paul E. Bierley, the author of The Works of John Philip Sousa, wrote, "Leading a harmonica band was a novel experience for Sousa when he was invited to conduct Albert N. Hoxie's fifty-two member Philadelphia harmonica band in September 1925. He was so impressed with their playing and the possibilities of the harmonica that he carried an endorsement for Hohner harmonicas in his 1928 programs and subsequently wrote this march for Hoxie's boys: The Harmonica Wizard. When the Sousa band came to Philadelphia on November 21, 1930 the mayor proclaimed the day: Sousa Day.

"Among other events was Sousa's leading the University of Pennsylvania band, but the climax of the day was when Hoxie's boys came to the stage during the Sousa band concert and performed the new march Sousa had written for them. A special commemorative medal with the emblem of the Philadelphia Harmonica Band on one side and a tribute to Sousa on the other was presented to the march king at the close of the concert."

The chromatic harmonica, introduced in the 1920's and championed in the 1930's by the virtuoso player Larry Adler (b. 1914), was the single most significant improvement in the evolution of the instrument; it directly led to the harmonica's acceptance and use by classical composers. During one of Adler's concerts, Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) was present in the audience. After the performance ended, Adler asked the celebrated English composer to write a piece for him; thus was born the beautiful Romance in Db (1952) for harmonica, piano and string orchestra.

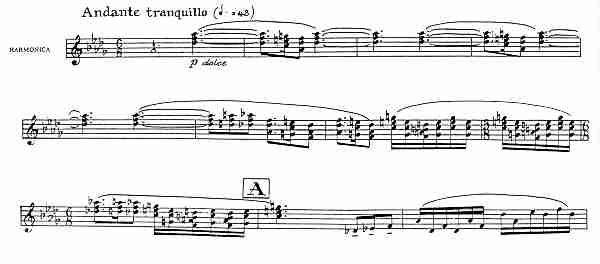

Example 5. Ralph Vaughan Williams,

Romance for harmonica, piano and

string orchestra,

measures 1-11 from the harmonica part.

© 1953 by the Oxford University Press, London.

Reproduced by permission of the publisher.

In 1942 Darius Milhaud wrote Suite Anglais, op. 234 (Gigue, Sailor Song and Hornpipe) for Adler, which was premiered by the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Eugene Ormandy. Many other composers wrote for Adler, including the British composers: Graham Whettam (b. 1927), who wrote Concerto Scherzoso op. 9 (1951); Malcolm Arnold (b. 1921), who wrote Concerto for Harmonica and Orchestra, op. 46 (1954); Gordon Jacob (1895-1984), who wrote Divertimento (1957); the Australian born Arthur Benjamin (1893-1960), who wrote Concerto (1953); and the Russian-born Francis Chagrin (1905-1972), who wrote Romanian Fantasy (1956). Other composers who wrote for Adler were Serge Lancen, who wrote Concerto (1958), Cyril Scott, who wrote Serenade (1936), and Jean Berger, who wrote Caribbean Concerto (1940).

Besides Adler, two other harmonica players were prominent in classical venues: John Sebastian and Tommy Reilly. Composers who wrote for Sebastian were: Edward Robinson, who wrote Chilmark Suite (1940) for F harmonica and Gay Head Dance (1941) for G harmonica; the Swedish composer, Walter Anderson, who wrote Fantasy for Harmonica (1947); the Brazilian composer, Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959), who wrote Concerto for Harmonica and Orchestra (1955-6); Luciane Chailly, who wrote Improvisation No. 9 (1963); the Russian composer, Alexander Tcherepnin (1899-1977), who wrote Concerto for Harmonica and Orchestra op. 86 (1953); and the German-American composer, Frank Lewin, who wrote Concerto for Harmonica and Orchestra (1960). Four American composers wrote for Sebastian: George Kleinsinger (1914-1982), who wrote Street Corner Concerto (1942); Norman Dello Joio (b. 1913), who wrote Concertino for Harmonica and Orchestra (1948); Alan Hovhaness (b. 1906), who wrote Concerto No. 6, op. 114 (1953-4) and Greek Folk Dances (1956); and Henry Cowell (1897-1965), who wrote Concerto for Harmonica and Orchestra (1962).

Composers who wrote for Reilly were: the British composer, Michael Spivakowsky (1919-1983), who wrote Concerto (1951); Graham Whettam who wrote Fantasy (1953) and Second Concerto op. 34; Gordon Jacob, who wrote Five Pieces (1957) for harmonica and piano (also arranged for harmonica and orchestra), James Moody (1907-95), who wrote five works: Quintet for Harmonica and Strings (1972), Irish Fallen, Dance Suite Francais, Toledo, and Little Suite; Fried Walter, who wrote Ballad and Tarantella; the Canadian-born British composer, Robert Farnon (b. 1917), who wrote Prelude and Dance; the Czech composer, Vilem Tausky, who wrote Concertino; and Karl Heinz Koper, who wrote Concerto op. 12 (1961). The Canadian composer, Milton Barnes (b. 1931), wrote Magic Miniatures (1983) for solo harmonica and Concerto for harmonica and strings.

Another concert harmonicist, Douglas Tate, has had many works written for him, such as: Sonatina for harmonica and piano, and Rhapsody for harmonica and piano by Peter Jenkyns (1921-1996); Apparitions for tenor voice, harmonica, piano and string quartet, Sonata for harmonica and piano (1968), and Sonatina Pastorale for harmonica and harpsichord (1972) by Phyllis Tate (1911-1987); Sonata for harmonica and piano by Madelaine Dring; Sonata for harmonica and piano (1970) by Arnold Cooke; and Quasi — a suite for harmonica and guitar (1972) by Patrick Harvey.

Five German composers who wrote for the harmonica were: Hugo Herrmann (1896-1967), who wrote Concertino (1948); Rudolf Wurthner, who wrote Intermezzo Giocoso (1957); Walter Girnatis, who wrote Concertino; Alfred von Beckerath (1901-1978) and Gerhard Anders-Strehmel. The French composer, Henri Sauget (1901-1989), wrote The Garden's Concerto (1970) for Claude Garden; the American composer, Robert Russell Bennett, wrote Concerto (1974); A. J. Potter wrote Concertino (1967); Leo Diamond wrote Skin Diver Suite (1956); and Richard Hayman wrote Concerto (1978). The Czech composer, Rudolf Komorous (b. 1931), wrote Rossi (1975) for chamber orchestra, which included a part for bass harmonica. The Canadian composer, Thomas Schudel, wrote Three Preludes for Harmonica and Piano (1987).

The American composer, Donald Erb (b. 1927), wrote Quintet (1976) for flute doubling on harmonica, clarinet, violin, cello and piano doubling on electric piano with a phase shifter attached. The members of the ensemble also perform on crystal water goblets. Erb also wrote Aura (1984) for string quintet. The violist is required to play a harmonica in C in addition to two water tumblers tuned a perfect fifth apart.

Despite the apparent success of the harmonica as a classical instrument, it is still not considered a serious instrument in classical music circles. Larry Logan — one of the premiere concert harmonicists alive today — wrote in The Harmonica Educator, "After forty-eight years on the stage here and abroad, if anyone would ask me today, 'Would you do it again?' I would probably say, 'I don't think so.'

"Interest in [the classical harmonica] novelty began in my generation with Larry Adler. With due respect to all his great talent, his rise to fame consisted of all the right ingredients: the times (the golden era of show-biz) and a monumental fluke that catapulted him to prominence by the name of [the agent] Charles Cochran. . . . The irony of this tremendous break for Adler, is that . . . Cochran was impressed not so much with Adler's playing of the mouth-organ, but with the idea that Adler was playing the mouth-organ dressed in a dinner jacket. . . . As a result, Cochran invited him to England, produced a review around him, and introduced his unique attraction to British royalty. The rest is history."

Logan continued, "As for symphony engagements, conductors . . . know very little of the harmonica's history. . . . When they engage a harmonica soloist in a concert, they are not engaging the soloist because they respect his virtuosity on the instrument, or because he has a long history on the legitimate stage. They are engaging the harmonica soloist because he has [had] an original composition for harmonica and orchestra written [for him] by some famous contemporary composer. You see, they are engaging the harmonica artist only because they are intrigued by the composer writing for this little rube instrument."

| Back to History of the Free-Reed Instruments |

| Back to The Classical Free-Reed, Inc. Home Page |