| The Classical Free-Reed, Inc. History of the Free-Reed Instruments in Classical Music |

|

Asian Free-Reed Instruments by Henry Doktorski (© 2000) |

| Part One: The Chinese Shêng |

|

Illustration 1: The Naw. Photograph by Randy Raine-Reusch To see a close up view of this image Click Here (21 KB) |

The evolution of the accordion began many thousands of years ago in

prehistoric Southeast Asia. The naw, which is played today by some of the

"Hill Tribes" of minority peoples found in Southern China and in the

mountains of Northern Southeast Asia, is in all probability the oldest

member of the free-reed family. It has five pipes grouped in a circular

cluster, whose open ends appear flush with the bottom of the gourd wind

chamber, which allows the player to "bend" notes by slowly covering the

ends of the pipes with the right thumb while playing. The technique for

this instrument is difficult and the resulting music is quite loud, in

spite of the bamboo reeds. Traditionally this instrument also played a

coded language which was used by unmarried couples in order to communicate

with each other.

(End note 1)

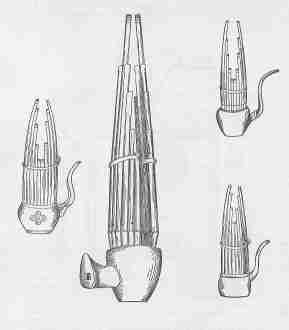

| Illustration 2: Four Shêngs. From J. A. Van Aalst, Chinese Music (New York: Paragon Book Reprint Corp., 1964), 81. To see a close up view of this image Click Here (5 KB) |

Another ancient text, the She-king, stated:

The drums loud sound, the organ swells

Their flutes the dancers wave.

(End note 3)

| Illustration 3: A shêng excavated from Marquis Yi's tomb (430 B.C.) This tomb, excavated in 1978, is located in what is now Hubei Province. Inscriptions on the bronzes found at the site identify the tomb as that of Marquis Yi of the state of Zeng in the early Warring States period around 430 B.C. Photograph from: Zuo Boyang, Recent Discoveries in Chinese Archeology (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1984), 8th page of illustration. (End note 4) |

The shêng, and its sister instrument, the yu, played significant

roles in ancient court and banquet orchestras. The shêng was especially important in

Confucian ceremonial music until the twentieth century when these rituals

themselves became obsolete. It was also played in secular contexts to

accompany folk songs, as a solo instrument and in operatic genres such as

k'un-ch'ü. The pronunciation of the Chinese character for the

musical instrument "shêng"

is the same as the pronunciation of another Chinese character "shêng"

(rising). Therefore the instrument implies luck and auspiciousness.

is the same as the pronunciation of another Chinese character "shêng"

(rising). Therefore the instrument implies luck and auspiciousness.

|

Illustration 4: Third century B.C. line-drawing. From T.C. Lai, Jade Flute: The Story of Chinese Music (New York: Schocken Books, 1981) 50, 51. To see a close up view of this image Click Here (38 KB) |

| Illustration 5: An undated depiction of an all-women's

ensemble from the Tang dynasty. Photograph courtesy of Robert Garfias, from http://aris.ss.uci.edu/rgarfias/gagaku/banquet.html. |

All-women orchestras were sometimes employed for court ceremonies. Orchestras from many parts of Asia were invited to perform in the court and many of these ensembles became a regular part of Tang entertainments.

The shêng is constructed of four parts: the base (wind chamber), the

mouthpiece, the pipes and the reeds. It originally had a gourd

(End note 6)

as a wind-chamber. Later shêngs had bases made from lacquered wood; today

modern shêngs have bases made from metal. The shêng had thirteen to

twenty-four bamboo pipes. (Seventeen pipes was the standard number.) At

the base of each pipe a tongue (made from a copper alloy)

(End note 7)

was cut in such a way as to vibrate freely when the player blew into the

instrument through the mouthpiece and covered the hole in the side of a

pipe with a finger. The shêng was formed to imitate the shape of the tail

of the Phoenix bird — fêng-huang — and the length of the pipes

has no effect on the pitch; the shape is simply decorative.

| Illustration 6: Another

shêng excavated from Marquis Yi's tomb (430 B.C.)

Photograph from Zhongguo Gu Wenming [Ancient Chinese

Civilization] (Taipei: Hankun wenhua shiye youxian gongsi, 1983), 51,

courtesy of Dr. Ping Yao, California State University, Los Angeles.

To see a close up view of this image Click Here (9 KB)

To hear music performed by this instrument Click Here

|

| Illustration 7: Yu and

Shêng in the style of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.), manufactured by

Suzhou #1 Traditional Musical Instrument Factory.

Photograph taken by the Oriental Musical Instrument

Exhibition Hall, Shanghai Conservatory of Music and provided by Yu Hui,

Music Research Institute, Shanghai Conservatory of Music.

To see a close up view of this image Click Here (11 KB) |

| Example

1: Hantian Lei in Gongche notation

(20 KB) |

| Example

2: Hantian Lei in modern notation

(48 KB) Transcribed by Alan Robert Thrasher |

Very few people can read Gongche notation anymore, even professional shêng players. Today, shêng players are trained to read modern staff notation, as well as tablature, which uses numbers and other symbols to indicate the pitches and rhythms. The following example is a type of tablature which originally came to China from the West via Japan.

| Example

3: Jin-Diao (Music from Shanxi Province)

by Yan Haideng (26 KB) Modern Tablature |

| Example

4: Jin-Diao (Music from Shanxi Province)

by Yan Haideng (36 KB) Modern Notation |

Jin-Diao is based on musical material of the Shanxi regional theater (Shan-xi-bang-zi) and includes characteristic techniques such as li-yin (glissando) and tu-yin tonguing.

During the second half of the twentieth century, improvements were made to the shêng. There are now shêngs with 36 and 51 pipes (with keys to extend the range of the fingers), as well as amplified shêng, alto shêng, bass shêng and keyboard shêng. There are also chromatic shêngs which allow the performer to modulate to different keys as well as play complicated chords and polyphonic passages. The bass shêng, also known as BaoShêng, is large and heavy and has to be placed on the lap or on the floor. Its sound is low and mellow and it can produced a great variety of chords. Steel tubes are used instead of bamboo tubes, for large bamboo tubes that resonate low pitch notes are difficult to find.

|

Illustration 8: A modern improved shêng: BaoShêng

Photograph taken by the Oriental Musical Instrument Exhibition Hall,

Shanghai Conservatory of Music and provided by Yu Hui, Music Research

Institute, Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Notice the 36 buttons.

To see a

close up view of this image Click Here (9 KB) |

The following musical example gives an indication of the high standard of technique required by contemporary shêng players. Note the three-note triad drone accompanying a single line melody with many grace notes in the first eight measures. Also of interest is the single line melody accompanied by syncopated three-note chords in lines nine and ten.

| Example 5: Happy Woman Soldiers (31 KB) |

As in the past, the shêng today is still an integral part of the cultural

life of the Chinese people. The modern Chinese orchestra consists of four

sections: woodwind, string, plucked string and percussion. The string

section consists of instruments like the GaoHu, ErHu, ZhongHu and

occasionally, a BanHu. The plucked string section consists of

instruments like the LiuQin, Pipa, Zhong Ruan, Da Ruan and

occasionally, San Xian. In the woodwind section are instruments

like Dizi (Bangdi, Qudi and Xindi), Suona and

Shêng. The percussion section consists of instruments like the

Chinese drums, gongs and timpani. The modern Chinese orchestra uses the

cello and double bass to strengthen the bass composition of the orchestra.

Before the introduction of these Western musical instruments the main bass

string instrument was the GeHu. Other instruments include the

Konghou (harp), Zheng (zither) and Yangqin

(hammered dulcimer).

(End note 8)

Very few shêng players have concertized in the West. Wang Zheng Ting (b.

1955) is a graduate of the Shanghai Conservatory and holds an M.A. degree

in Ethnomusicology from Monash University in Australia. He is the founder

and director of the Australian Chinese Music Ensemble and has actively

promoted Chinese music throughout that country. His 1997 US tour

included both lectures at various universities and the premiere in

Minnesota of his Concerto for Sheng, commissioned by the American

Composers Forum. Wang is presently pursuing the Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology

at the University of Melbourne. I had the pleasure of meeting him and

hearing him perform in 1999 at a

concert

in New York City sponsored by The Center for the Study of Free-Reed

Instruments (Graduate School and University Center of the City

University of New York).

|

Illustration 9: Wang Zheng Ting holding a modernized Hmong gaeng.

Note the megaphone-like bells at the ends of the pipes

to enhance the projection of the sound. (End note 9) To see a close up view of this image Click Here (30 KB) |

| Example 6: Wang Zheng Ting, Concerto for Shêng (cadenza) (47 KB) |

Many modern Chinese composers have written for the instrument. Following are some composers and their compositions for shêng and traditional Chinese orchestra which were recorded on a compact disc titled Shêngmasters and released by the China Record Corporation in Shanghai: Li Zuoming wrote Spring Song on the Xiangjiang River, Yan Haideng wrote Jin-Diao (Shanxi Tune), Xiao Jiang and Mou Shamping wrote Riding a Bamboo Pole, Xu Chaoming wrote Moon Night in Lin-Ka, Liu Yu wrote Butterflies Love Flowers, Mou Shanping wrote Lotus Flower Above the Water, Gan Yang and Qingchen wrote The Reservoir Attracts the Phoenix. As can be deduced from the titles of these pieces, a natural love for nature is reflected in Chinese traditional music.

A few Western composers have also expressed an interest in the shêng. In 1963, the American composer, Lou Harrison (b. 1917), composed a large work for an orchestra of Western and Oriental instruments: Pacifika Rondo. It is scored for shêng, psalteries, p'iri (a Korean double-reed instrument), chango (a Korean hourglass-shaped doubled-headed drum), and a pak (a Korean wooden clapper) along with Western stringed instruments, celesta, trombones, organ, percussion, and tin whistles.

End Notes

1. In mainland China, the Naw is called Hulushêng. I did not

use this term in this chapter as Hulushêng is a derogatory Chinese term

for the free-reed instruments of the "National Minorities," which

translates into something like "barbarian shêng."

2. She-king, II, I, I, cited by Dr. F. Warrington

Eastlake in China Review (published August 1882), and reprinted

in the book by J. A. Van Aalst titled Chinese Music (New York:

Paragon Book Reprint Corp., 1964) 81.

3. She-king, II, VII, VI, Eastlake, op.

cit.

4. The tomb of Marquis Yi is 21m long, 16.5m wide, 13m deep,

making it 220 square meters in area. It has four chambers. The central

chamber was decorated as a ceremonial hall with a set of bronze bells

still hanging on their rack and bronze vessels neatly arranged in rows.

The north chamber resembled an armory with large numbers of weapons,

chariot trappings, helmets, and armor. The east chamber contained the

coffin of the Marquis Yi and a large number of musical instruments. 21

smaller coffins in the tomb were also found in the eastern and western

chambers. All belong to young women between the ages of 13 and 25.

Altogether Marquis Yi's tomb contained:

From: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, A Visual Sourcebook of Chinese

Civilization, Test Version. (University of Washington website:

http://depts.washington.edu/visualsb/archae/2marmusi.htm)

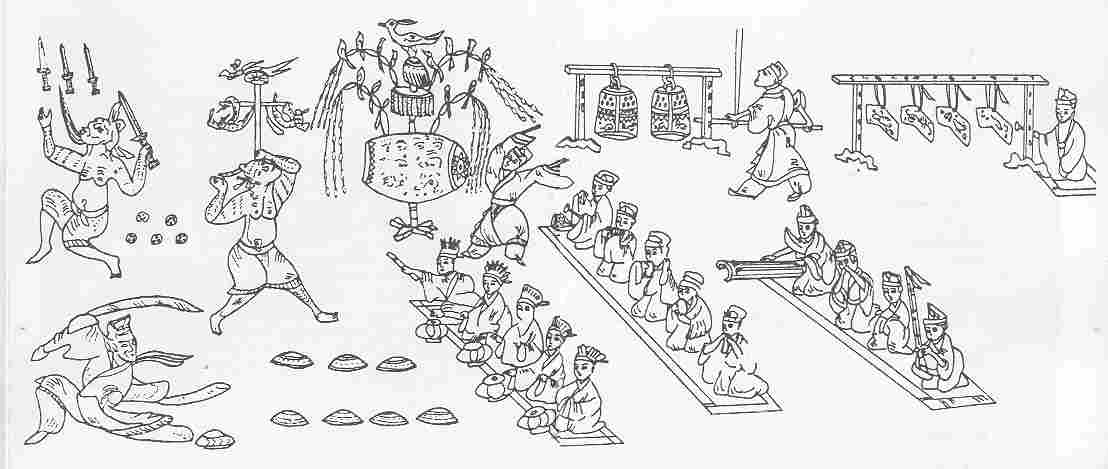

5. Three rows of musicians are shown sitting on mats. In the

first row are four women singers accompanying themselves on the Wa

P'ing (earthen hand drum) while the fifth appears to be beating time

with a stick. In the second row are performers of the Hsün

(globular clay flute), Pai Hsiao (pan pipes) and Nao

(single large bell). In the third row, one musician plays the Yu

(mouth organ), another the Se (zither), while another seems to be

playing a kind of Jew's harp (possibly with a leaf as the reed — "Chu

Yeh").

At the back of the orchestra, three percussionists play one Chien Ku

(barrow drum) mounted on an elaborate stand, two large bells and four

stone chimes. The dancer with large sleeves in the foreground is looking

back toward seven drums (Pan Ku) on the ground which he will mount

and stamp in time to the music.

6. Musical instruments were classified by the ancient Chinese

according to eight varieties:

7. Terry E. Miller wrote, "The reeds are made, I'm told, from

cutting up old gongs."

From an email letter to the author, June 20, 2000.

8. Diagram from the Singapore Chinese Orchestra website: http://www.sco-music.org.sg

9. The Sinocentric mainland Chinese people pejoratively call this instrument Lushêng, or

"barbarian shêng."

10. Wang Zheng Ting, from an e-mail letter to the author.

125 musical instruments, including bells, drums, zithers, pipes, and

bamboo flutes

134 bronze vessels and daily use items

4,777 weapons, mostly made of bronze

1,127 bronze chariot parts

25 pieces of leather armor

5,012 pieces of lacquer ware

26 bamboo articles

5 golden vessels and 4 golden hooks

528 jade and stone objects

6,696 Chinese characters written in ink on slips of bamboo

1) stone (the stone-chime)

2) metal (the bell-chime)

3) silk (the lute)

4) bamboo (the flute)

5) wood (the tiger-box)

6) skin (the drum)

7) gourd (the shêng)

8) earth (the porcelain-cone)

The Japanese Sho The Laotian Khaen

Back to History of the Free-Reed

Instruments

Back to The Classical Free-Reed, Inc.

Home Page